Sri Lanka has entered into a period of conflict transformation. The theory of conflict transformation states that conflict changes the parties, their relationships and issues over time. There is a new relationship and the issues at hand can be addressed at a different level. This offers the chance to resolve the problem in a new way. The defeat of the LTTE on the battlefield and the Rajapaksa government in elections has created a big change in the environment. The way that the government handles inter-ethnic relations today is different from that of the past. The top leadership of the present government, President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, and also leading government figures such as Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera, do not see the Tamil and Muslim people separately from the Sinhalese. Their approach is to see the people as one, rather than in terms of their ethnicity or region.

The downfall of the Rajapaksa government occurred because the former government saw national politics in ethnic terms. They considered the Tamil and Muslim people not only as distinct from the Sinhalese people to whose interests they gave priority, they also saw them as potential threats to national security. This is why the security forces were permitted to remain inactive even while Sinhalese mobs attacked Muslim properties, as in Aluthgama. This is also why the former government sought to increase the size of the Sri Lankan security forces after the end of the war, instead of demobilizing them as is common when a war ends. Instead of seeking to build a new future based on the peace that had been achieved, they began to prepare for another conflict in the future. The former government had a securitization mindset which impelled them to see national security as requiring a watchful eye and a military presence over the ethnic minorities.

The non-ethnic approach to governance that the present government leadership has shown is being reciprocated by the ethnic minority political parties. They are by and large fully supportive of the government and are placing their trust in its commitment to resolve long standing problems. Even those groups that continue to believe in the need for pressure to be put upon the government in the form of people’s power, such as the Tamil People’s Council in Jaffna, have made an effort to inform their supporters that they are neither being anti government nor anti Sinhalese. The large demonstrations that took place in Jaffna last week highlighted concerns about the non-return of land taken over by the military, the release of prisoners incarcerated for years without charge and the putting up of Buddhist symbols in places where there are no Buddhists. But there also needs to be a recognition of how much has changed for the better in the past one and a half years.

PEACE BUILDING

The day before Tamil People’s Council held its rally there was a sports programme in Jaffna organized by Netball Australia in collaboration with the Foundation for Goodness in which cricket star Muttiah Muralitharan is a leading figure. Coaches and students from six schools each in Jaffna and Galle were the beneficiaries of this programme where their netball playing skills were enhanced and they were given a broader perspective about living together peacefully in one country. This programme involved coaching school children, along with their coaches, in the latest techniques in playing netball. The programme also had a peacebuilding component which was facilitated by the National Peace Council together with the Centre for Communication Training. Such people-to-people initiatives have been found to be useful in rebuilding broken relationships in post-war societies.

The representatives from Netball Australia expressed their satisfaction that both the coaching and relationship building exercises had taken place successfully. They said that a similar programme carried out in an African country had run into difficulty as the children from the two conflicting communities had refused to sit together. This is indicative of the advantage that Sri Lanka has in seeking to strengthen post-war reconciliation and unite the people of the country. In Sri Lanka it may be generally observed that children, and also adults, of the different ethnic and religious communities, tend to get on well with each other in social and professional spaces. This was the case even during the height of the war for the most part. By contrast, even in Northern Ireland today, two decades after the violence has ended, and a political solution has been found, the social gap between the communities is still wide. In Sri Lanka, this social gap is less wide.

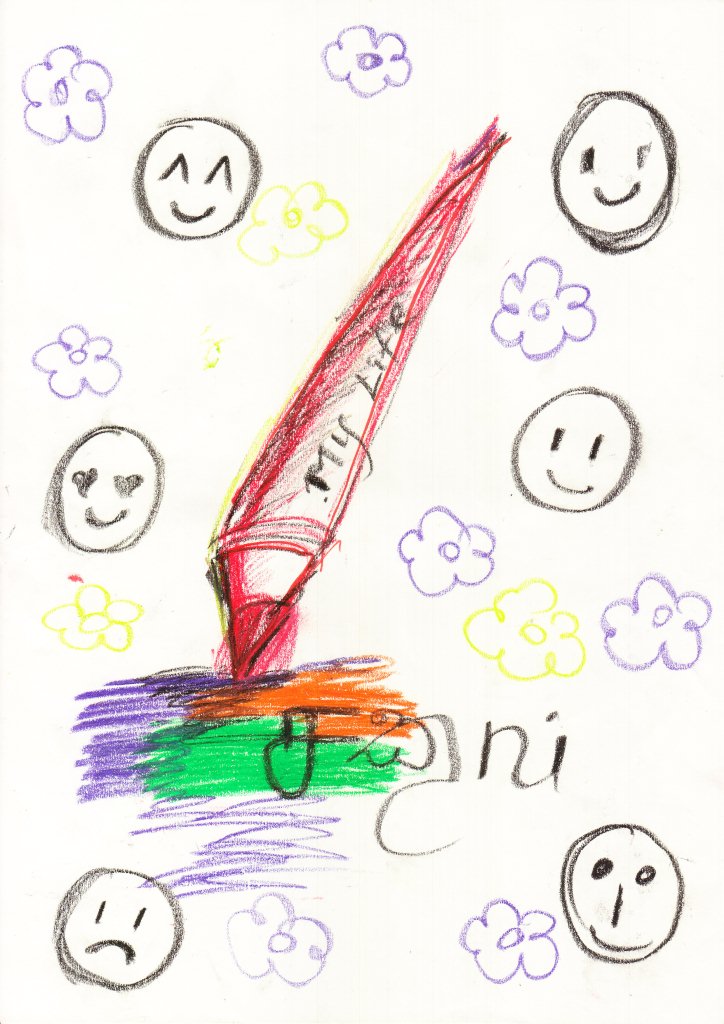

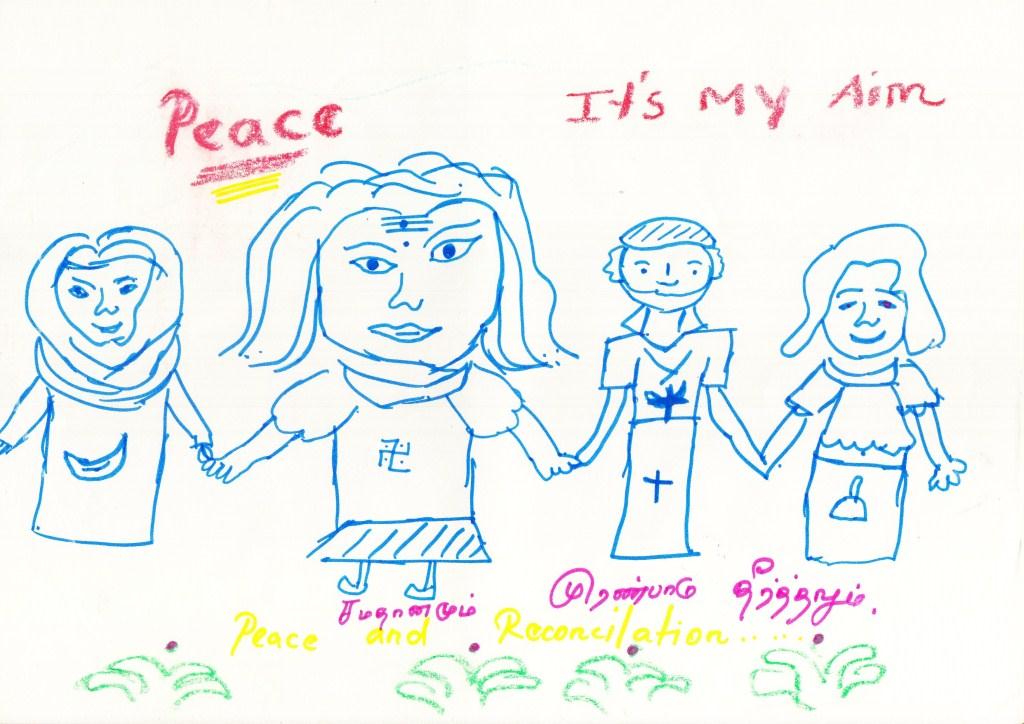

A demonstration of the goodwill that naturally exists between the different communities was manifested in an exercise that the students were asked to undertake by the facilitators from the Centre for Communication Training. The children from the north and south were put into mixed groups and were each asked to draw a picture which described what they are, wish to be and hope to become. They were also asked to explain their drawings to those in their group. Although most students could not speak in the language of the other community, they somehow struggled to explain what their drawings meant to each other, including using whatever English they knew as the link language.

One child drew a pen and wrote letters in the Sinhala, Tamil and English alphabets. She explained that she was the pen, and writing her own life, and it would be lived in the three languages.

Another child drew figures of people belonging to the four religions and said she would be a worker for peace.

PUBLIC EDUCATION

The government leadership is presently charting out a roadmap to reconciliation in Sri Lanka along with the political leadership of the Tamil and Muslim parties. There are two important processes taking place that are intended to lead to the development of a new constitution and the establishment of reconciliation mechanisms. Both are going to be public processes. The constitutional reforms will have to be approved by the people at a referendum. The reconciliation process will also be a public one as it includes the setting up of a truth seeking commission, the proceedings of which will be seen and heard by the entire country. Both of these processes will also go deep into the most controversial areas of public and political life, such as the devolution of power and the charges of serious human rights violations and war crimes connected to the war.

Last week, parallel to the netball programme in Jaffna, the National Peace Council held a workshop on transitional justice at Eastern University in Batticaloa. There were about a hundred students drawn from the Tamil, Sinhalese and Muslim communities in approximately equal numbers. In their group discussion when they were asked to list their priorities in terms of reconciliation, irrespective of ethnicity, the students said that the law must apply equally to all, regardless of status or ethnicity. They also recommended having educational campaigns on the important reform processes within the country or else they said that politicians and others will exploit the ignorance of the people. Although they were divided into mono-ethnic groups, in which all the students in a group were of the same ethnicity, they took care not to hurt the sentiments of those of other ethnicities.

However, it was a matter of concern that none of the students said they were aware of the public consultations process that had taken place with regard to both constitutional change and the reconciliation mechanisms. There is an emerging vulnerability in the ongoing reconciliation process due to this lack of public awareness and public participation in the reforms that are being initiated at the highest levels of the polity. The first is that nationalist propaganda can fill in the vacuum. Among them are charges made by the Tamil People’s Council is that there is Sinhalese colonisation of Tamil lands and the building of Buddhist temples in these areas. Charges that give emotives or misleading interpretations about the reforms that are taking place are made in the South as well. The possible resurrection of the LTTE due to the actions of the government and the division of the country by the international community are some of the favourite propaganda lines. Unless countered effectively this can lead to a loss of trust and confidence and back to a negative cycle of renewed conflict. The best way forward would be to engage in greater awareness education and to find ways to make community leaders participate directly in the reconciliation process by means of people-to-people engagements.