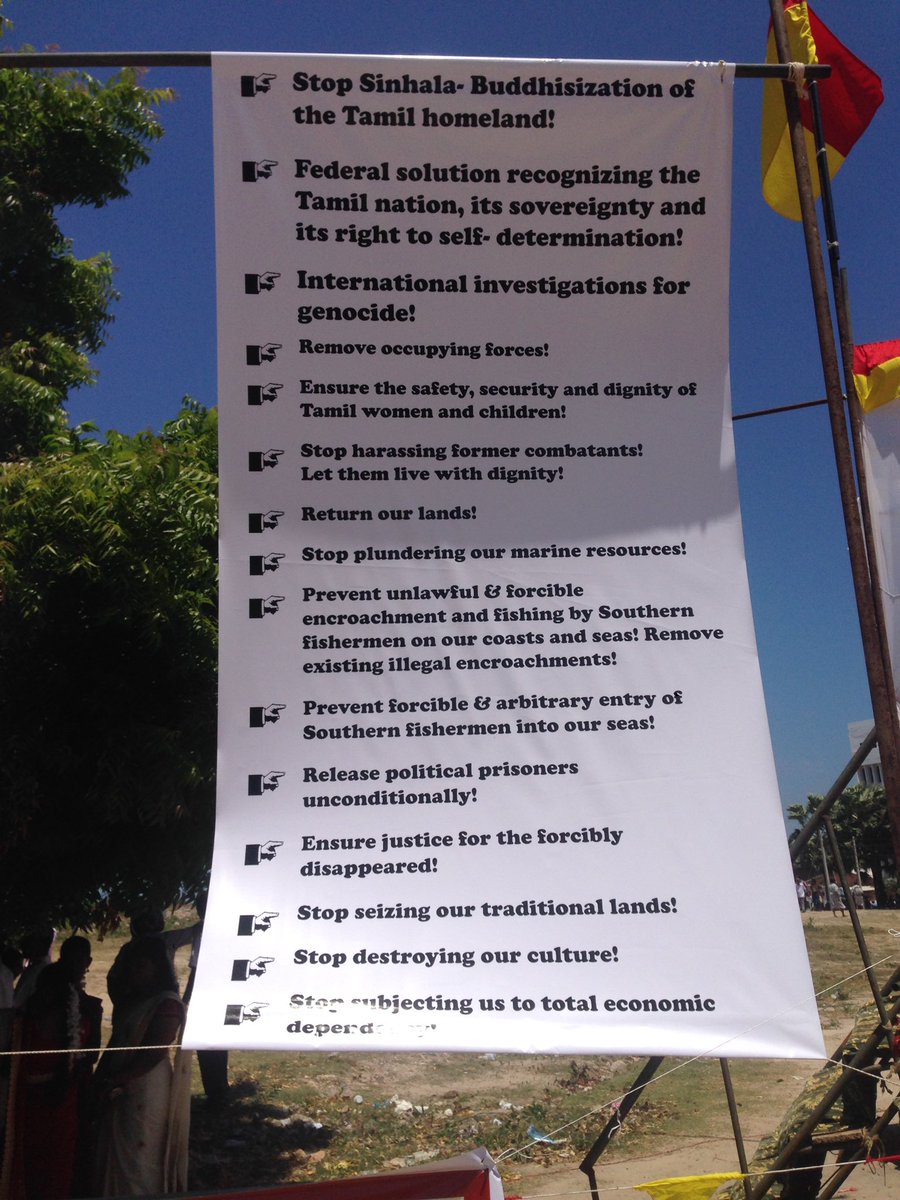

The furor over the the Eluga Thamil (Tamils arise) rally that took place in Jaffna last month is receding. At those protests a powerful and angry people’s movement was in evidence, led by Northern Province Chief Minister C.V. Wigneswaran, and organised by the Tamil People’s Council (TPC), an organisation that the Chief Minister heads. In addition, several Tamil political parties, including some constituents of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) participated. The demands put forward by the organizers included a call for federalism with the rights to sovereignty and self determination of the Tamil nation recognized, return of land in the Army’s control, release of political prisoners, an international investigation into war crimes and addressing concerns relating to missing persons were prominent. There were also clear anti-south manifestations in the slogans, which included a call to halt to putting up Buddhist shrines in the North and a call to stop southern fishermen, but without a mention of the massive encroachments by Indian fishermen.

The day prior to the Eluga Thamil rally in September I visited the University of Jaffna to discuss the holding of workshops on the ongoing national reconciliation process for both faculty members and students. I was introduced to them by the Centre for Women and Development in Jaffna, headed by Saroja Sivachandran. In both the North and South, the universities have been hotbeds of radicalism and not only seats of learning. In a context where the forces of narrow ethnic nationalism continue to be active, this radicalism tends to take an ethno-centric dimension. In July, the University of Jaffna was in the news after a clash between two student factions over cultural symbols resulted in a number of injuries. The violence was severe enough for the Sinhalese students to set off for their homes in the South while the university remained closed for several days. Although reports of university students engaging in clashes is not an uncommon phenomenon in Sri Lanka, this particular turn of events received more than the usual amount of speculation and most of the debate was centred on the issue of ethnicity, which in turn triggered negative sentiments.

WILLINGLY COOPERATE

Therefore it was with some reservations that we entered into the university premises. We wanted to discuss the concepts of transitional justice which are now standard UN mandated prescriptions for countries which are in positive transition from a worse situation of war and human rights violations to a better situation of peace and justice. In addition, we wanted to discuss the government’s own four-fold mechanisms for reconciliation which comprises a Commission on Truth Seeking, an Office of Missing Persons (law passed but not yet implemented), Office of Reparations and Institutional Reforms that aim to ensure that the past will not recur again (constitutional change). What was interesting was that some of the University of Jaffna faculty members who were actively involved in organizing the Elagu Thamil rally also readily agreed to cooperate with us in securing a viable venue and a suitable environment for the educational workshops to be held.

It might have been expected that the discussion on reconciliation being undertaken by the government would lead to a critical and challenging engagement for those of us who had come from the South to organize the workshops. We were going to be discussing the highly contested issues of transitional justice which includes missing persons, land being taken over, resettling internally and externally displaced persons in their own lands to the extent possible and the perennially controversial issue of devolution of power. One of the groups we were going to work with was the very same faculty members who had been part of the organization of the Eluga Thamil event. The other group we were going to work with was the students from a student body that had clashed violently between themselves.

Nearly 50 faculty members and 60 students of the University of Jaffna attended the two workshops on transitional justice. Belying our concerns about a possibly hostile reception to the ideas on reconciliation we had, they were generally receptive to the ideas put forward and willing to discuss them in an engaging and frank manner. They had their concerns and criticism which they shared with those who had come to conduct the workshops, which included Lal Wijenayake the chairman of the Public Representations Committee on Constitutional Reforms and Raga Alphonsus who was a member of the Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms. Both of them had firsthand experience of what the general public thought and felt about the two main political processes taking place in the country at this time. Therefore they were in a position to give the academic community a reality check.

FAMILY TOGETHER

At the end of each of the workshops there was the satisfaction, trust and even joy of engagement. We took many group photographs together. Some of the academics explained that they supported the Eluga Thamil event, but not all of its slogans. But before that there were hard questions asked. One question was whether the National Peace Council which sponsored the workshops was a government agent. Another question was why voices for peace were not heard by the people of the North during the time o f the war. A third question was why we active only now. Most NGOs such as the National Peace Council were never agents of the government, either this or the ones before. They strive to be non partisan with regard to political parties, either supporting or opposing what governments do or what political parties say on the basis of the positions they take. During the time of the war the voice of nationalism was dominant and the voice of peace groups was marginalized, but the work of building peace at the community level never stopped. We used different terms such as healing.

There were other questions too, such as why the army was trying to take over lands at the same time as it was handing over other lands. Although there were critical questions and comments, overall the discussion was constructive and cooperative with no one raising their voices or attacking anyone. The outcome of the student presentations shows that even the students, who are always more radical than their elders, were practical in their expectations. Transitional Justice has four pillars, or areas of focus. These are the search for the truth about what happened (Truth), accountability or punishment of those who broke laws (Prosecution), reparations or compensation (Reparations) for those who lost during the war, and institutional reform to ensure that the violations of the past will not happen again (Constitutional Reform). The students were asked to work in small groups of 5-8 students, and to say which one of those four pillars they would give their priority to. There were 9 groups that were formed.

If the predominant emotion of the students had been revenge or hatred, they would have chosen Prosecution as their first priority. However, not even one group chose Prosecution. Five of the nine student groups chose Constitutional Reform as their first priority. Those who chose Constitutional Reform said that was the long term solution, and if this was achieved the other three pillars of Transitional Justice could be achieved over time. Four of the nine groups chose Truth as their priority. They said that without Truth it is difficult to find out what the problem is, and what the best answer would be. It is necessary for the government to give clear and detailed answers, not only on questions of the past and what happened during the war, but questions about the present, including the suspicions that Sinhalese colonization is still happening with government patronage in the North. The message from the Jaffna workshops with the university community was that Sri Lanka can still be a family together, where each community and each individual is equally valued, and not a country divided.